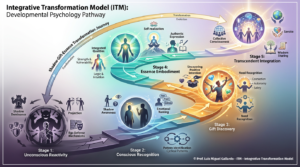

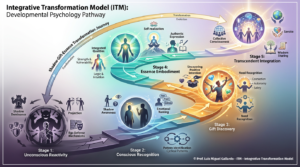

From Shadow to Essence: The Integrative Transformation Model (ITM) for Leaders and Changemakers

By Prof. Luis Miguel GallardoFounder & President, World Happiness FoundationProfessor

Nonviolence is more than the absence of war – it is a way of life and a strategy for building Fundamental Peace, grounded in justice, freedom, and human dignity. This comprehensive vision of peace goes beyond silencing guns to dismantling the deeper causes of conflict, including structural violence (oppressive systems) and cultural violence (beliefs that normalize harm). In a truly peaceful society, happiness and well-being are core priorities, not afterthoughts. Research supports this linkage: a study of global data found that more peaceful societies tend to have higher levels of happiness, and vice versa. In other words, fostering collective well-being through nonviolent means creates a positive feedback loop – happier communities are more peaceful, and peaceful communities enable greater happiness.

Adopting nonviolence is both morally visionary and intensely practical. History shows that nonviolent movements can achieve profound change more effectively and sustainably than violence. Seminal research comparing over 300 campaigns found that nonviolent resistance campaigns succeeded about twice as often as violent insurgencies in achieving social or political goals. Why? Peaceful movements invite broader public participation and avoid the destructive backlash that violence provokes. Communities built on trust and inclusion also prove more resilient and prosperous than those ruled by fear, as cooperation replaces coercion. In our personal lives too, choosing patience over anger and empathy over hatred yields better relationships and a more meaningful life. These outcomes underscore that nonviolence “works” – it not only prevents suffering but also produces more democratic, lasting solutions.

To harness nonviolence as a pathway to global well-being, we must embrace it at every level of society. The World Happiness Foundation emphasizes that nonviolence must be practiced “in all its forms – physical, psychological, or structural”. This means cultivating peace within ourselves, in how we treat others day-to-day, and in the policies and institutions that govern us. It requires nothing less than replacing our current culture of violence – which treats conflict and domination as inevitable – with a culture of peace where dialogue, compassion, and justice are the norm. As Martin Luther King Jr. taught, “true peace is not merely the absence of tension, it is the presence of justice.” Nonviolence strives to bring that positive peace into being by addressing injustice and healing the root causes of violence.

Adopting nonviolence begins with a fundamental mindset shift. Modern society often approaches problems with a scarcity mentality, framing social change as a “fight” against what we fear – fighting poverty, combating crime, waging war on drugs. This mindset fixates on what we lack and whom we must resist, which can breed fear, competition, and burnout. A nonviolent paradigm instead embraces an abundance mindset, asking what we can create together in the spirit of shared prosperity and well-being. The World Happiness Foundation calls this vision Happytalism – a development paradigm focused not on endless struggle but on co-creating conditions for collective happiness, peace, and freedom. In practical terms, this means shifting from solely opposing what is wrong to actively modeling and building what is right. For example, rather than only “fighting inequality,” a nonviolent abundance approach also builds inclusive economic systems that uplift everyone. Instead of merely resisting corrupt politics, it models transparent, participatory governance at the community level.

This shift from fighting to co-creating is powerful. When we define our work by what we are for, not just what we are against, it unleashes creativity and hope. An abundance mindset recognizes that compassion, ideas, and resources exist to meet human needs – especially when we collaborate rather than compete. It replaces the zero-sum thinking of scarcity (“if they win, we lose”) with an understanding that we are interdependent and can find win-win solutions. This outlook is evident in practices like community gardening to address food insecurity or time-banking exchanges of services – efforts that solve problems by strengthening cooperation and trust instead of inflaming rivalries. By focusing on co-creation, modeling, and transformation, we tap into what Mahatma Gandhi called the “constructive program”: building the new world within the shell of the old, here and now.

Crucially, a nonviolent mindset also means rejecting the notion that violence is “just human nature” or unavoidable. We must **stop treating violence as inevitable or as “realism,” and stop romanticizing domination as strength. Violence persists largely because it has been normalized – society trains us to accept cruelty, to see enemies instead of human beings, and to prioritize weapons over wellness. Nonviolence calls us to denormalize violence by actively questioning these narratives. It reminds us that might does not make right, and that true strength lies in empathy and self-mastery, not in coercion. As one peace leader wrote, “A world addicted to violence will always find a reason to justify it. A world healing from violence will find a way to outgrow it.” In practical terms, this means refusing to accept excuses for harm and instead demonstrating that conflicts can be managed through law, dialogue, and mutual respect.

Finally, the nonviolent ethos begins within each person’s heart and mind. Inner transformation and interpersonal compassion are the soil from which nonviolent action grows. Cultivating inner peace, empathy, and mindfulness makes us less likely to cause or tolerate violence around us. Indeed, “non-violence begins within”: if we heal our own traumas and fears, we are less prone to lash out or seek control over others. This is why practices like meditation, mindfulness, and Nonviolent Communication (NVC) are often taught alongside activism – they build the emotional resilience and understanding needed to respond to pain with patience rather than rage. In sum, a nonviolent mindset is one of abundance, empathy, and co-creative courage. It trades the fight-or-flight reflex for a proactive commitment to model the change we seek. With this orientation in place, we can turn to the practical methods of nonviolent action that translate vision into reality.

Nonviolence is not passive – it is an active force expressed through countless tactics and methods. Researchers and practitioners have identified hundreds of nonviolent tactics that people have used to resist injustice, promote change, and build alternatives (Gene Sharp famously catalogued 198 methods, and recent studies have added many new 21st-century tactics). These tactics range from protests and marches to boycotts, strikes, sit-ins, hacktivism, and creating parallel institutions. To make sense of this rich toolbox, it helps to categorize tactics by what kind of action is being taken and how it produces change. One useful framework classifies nonviolent actions into three broad types – acts of expression, acts of omission, and acts of commission – each of which can be carried out in a confrontational (coercive) or a constructive (persuasive) manner. In simpler terms: we can say something, not do something, or do something new – and each of those actions can either put pressure on an opponent or appeal to their conscience/offer solutions. The chart below outlines this framework with examples:

| Type of Action | Confrontational (Coercive) Tactics – pressure or disrupt to force change – | Constructive (Persuasive) Tactics – appeal, reward, or model to inspire change – |

| Expression (Saying something)Actions that express dissent or values publicly. | Protest and Nonviolent Persuasion: Communicative acts that criticize, dramatize, or challenge injustice to put moral and public pressure on violators.Examples: marches and rallies; picketing or vigils at sites of power; wearing protest symbols; mass petitions; street theater and satirical demonstrations that shame or expose wrongdoing. These actions send a loud message that “We do not consent” – they mobilize public opinion and erode the legitimacy of violence or oppression. | Appeal and Dialogue: Communicative acts that invite reflection or empathy, aiming to sway hearts and minds (including those of opponents or the broader community).Examples: formal statements and open letters; peace education campaigns; interfaith prayer services (e.g. multi-religious “pray-ins” appealing to shared values); art and music for peace (murals, songs conveying hope); humor and satire that undercut fear; offering flowers or gifts to soldiers or adversaries. These tactics model the compassion and understanding they wish to see, often softening attitudes and opening space for dialogue rather than confrontation. |

| Omission (Not doing something)Actions that withhold cooperation or refuse certain behaviors. | Noncooperation: Deliberate refusal to continue business as usual, in order to disrupt the status quo and impose costs on injustice.Examples: economic boycotts (refusing to buy or sell to withdraw resources from a system of harm); labor strikes (“downing tools” to halt production until conditions change); civil disobedience of unjust laws (openly defying rules to block their enforcement); social noncooperation (shunning corrupt officials or institutions). Noncooperation is a powerful coercive lever – by “not doing” what oppressors expect, people remove the pillars that violence and tyranny depend on. | Refraining: A less common but potent constructive omission – activists voluntarily halt or suspend a protest action as a gesture of goodwill or to persuade the opponent.Examples: declaring a temporary cease-fire or pause in demonstrations to encourage negotiations; ending a boycott after partial concessions as a reward/incentive; Gandhian “hartal” fasts or days of silence to invite the opponent’s conscience. Refraining tactics say “We choose to stop our pressure, conditionally, to give peace a chance.” They can de-escalate a conflict and appeal to the opponent’s better nature, signaling trust-building. (Historically, Gandhi sometimes suspended civil disobedience campaigns upon signs of progress – using restraint as a persuasive tool.) |

| Commission (Doing or creating something)Actions that intervene or introduce new behavior into the situation. | Disruptive Intervention: Direct actions that physically or materially disrupt ongoing unjust activities, thereby forcing change or at least drawing attention.Examples: sit-ins occupying segregated or illicit spaces (blocking “business as usual” to make oppression untenable); human blockades and barricades that nonviolently obstruct operations (e.g. blocking access to a weapons factory); cyber disobedience or hacktivism to expose secrets (whistleblowing leaks of classified abuses, website defacements to protest censorship); die-ins or other dramatic interruptions of public events. These tactics grab the wheel of history, directly interrupting harmful processes. They often involve personal risk and confrontational courage to say “We will stop this with our bodies, if need be.” | Creative Intervention: Direct actions that model and build alternatives, or creatively transform the conflict environment, offering a compelling preview of a better way.Examples: forming parallel institutions that meet community needs peacefully – alternative economies like local currencies or barter networks to reduce dependence on exploitative systems, or community-run “free schools” and clinics where the state fails; establishing peace zones or sanctuaries that forbid weapons (as some villages have done amid civil wars); holding mock elections or people’s assemblies to demonstrate democratic processes; Critical Mass bicycle rides reclaiming streets for eco-friendly transport. Even small creative acts count: planting trees in a degraded area (“guerilla gardening”), or the iconic image of protesters putting flowers in soldiers’ rifle barrels – all are constructive interventions. These tactics “prefigure” the future by living as if the peaceful, just society already exists. They persuade by example, showing that “another world is possible” and inviting others to join in building it. |

How do these tactics create change? Confrontational tactics (protest, noncooperation, disruption) work by nonviolent coercion – they raise the cost of oppression or disrupt it until those in power are compelled to negotiate or relent. Persuasive tactics (appeals, refraining, constructive programs) work by attraction and moral influence – they reduce fear, win hearts, and demonstrate solutions, so that opponents and bystanders choose to support change. Both approaches are vital. In fact, many effective nonviolent movements skillfully combine pressure and persuasion, confronting injustice while also offering a positive way forward. For example, civil rights activists in the U.S. not only staged protests and sit-ins to disrupt segregation, but also organized voter registration drives, created freedom schools, and practiced beloved community in their meetings – blending “Resist and Build”.

It’s important to note that these methods are highly adaptable. One tactic can often be used in either a more coercive or a more persuasive manner depending on context. A protest march, for instance, might feel confrontational with angry chants and civil disobedience, or it might be framed as a peaceful candlelight vigil appealing to conscience. Nonviolent strategists choose tactics to fit their goals, audience, and principles. The richness of the nonviolent “toolbox” – now spanning hundreds of tactics catalogued in research – allows movements to innovate. In recent years, activists have even leveraged digital tools for creative expression (think of hashtag campaigns and hackathons for social causes). The key is that all these diverse methods share a refusal to inflict physical harm. Instead, they use the power of people – their numbers, their solidarity, their ingenuity and sacrifice – as the force for change.

Practicing nonviolence is not only for activists in movements; it begins with how each of us conducts our daily life and relationships. Individuals can be powerful agents of peace by embodying nonviolent values in small but meaningful ways. As the old saying goes, “peace begins at home” – indeed, research in peaceful societies shows that everyday interactions rooted in respect and kindness are the building blocks of lasting peace. Here are some practical ways individuals can cultivate nonviolence in daily life:

In essence, practicing nonviolence as an individual comes down to living with integrity, empathy, and courage in everyday life. Each person’s consistent example of nonviolent values – however modest – contributes to a broader culture where violence is no longer seen as the default answer. As research on peaceful communities shows, peace is sustained by millions of daily positive interactions outweighing negative ones. Every time you choose understanding over aggression, you add to that balance. By making nonviolence a personal habit, we each help “be the change” and lay the groundwork for larger social transformations.

While individual action is critical, nonviolence truly flourishes when communities organize together. Communities – whether neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, or entire societies – can adopt strategic models of engagement to promote peace and justice. Below are key approaches for practicing and spreading nonviolence at the community level, along with practical examples:

The practices above form a practical, handbook-style framework that individuals and communities can use to make nonviolence a reality. By integrating hundreds of nonviolent tactics – from protests and strikes to alternative institutions and education – with an abundance mindset, we shift from a paradigm of fighting and resisting to one of co-creating, modeling, and transforming our world. In doing so, we actively de-normalize violence at every turn: in our own hearts, in our cultural narratives, and in our social structures. We replace it with norms of empathy, justice, and shared happiness.

This journey is both challenging and deeply rewarding. Nonviolence asks us to have faith in the best of humanity – to believe, as Dr. King did, that unarmed love is “the only way to ultimately overcome” and that hate cannot drive out hate. Yet nonviolence is far from naive. It is often called “a hard-nosed realism of hope”: it recognizes that lasting safety and happiness come not from dominating others, but from building conditions where everyone can thrive. Indeed, empirical evidence and historical experience align with this truth: societies that prioritize well-being, fairness, and dialogue tend to be more peaceful and stable. Conversely, violence and coercion breed only fear, resentment, and more violence.

The World Happiness Community envisions a future where Fundamental Peace – peace built on freedom, consciousness, and happiness – is the norm, not the exception. Achieving this means each of us becoming a guardian of that peace in our own sphere, and all of us working together to transform our communities. The framework in this guide is a starting point: use it to spark ideas, to plan initiatives, and to inspire others. Create study circles to learn nonviolent tactics and their successful examples. Encourage local organizations to adopt these practices and principles. Share stories of nonviolence working, because hope is contagious.

Above all, lead by example. When nonviolence becomes a living practice – when we consistently choose respect over rage, creativity over cruelty, and justice over indifference – it spreads. Bit by bit, the “normal” in society shifts from violence to compassion. As one manifesto declared, “Humanity must stop treating violence as inevitable… We must stop calling it ‘realism.’”. Instead, we embrace the truly realistic path: addressing our problems at their roots and holding fast to our shared humanity.

In a world where nonviolence is the beating heart of our global community, future generations will inherit a legacy of friendship, cooperation, and love. They will live free from fear and full of joy, grateful that we chose construction over destruction. This is not utopia – it is an attainable horizon, built one action at a time. Let us continue to aspire and act, so that the light of Fundamental Peace and global happiness grows brighter with each passing day.

In the words of the World Happiness Foundation’s call: Walk the path of peace, compassion, and love. Choose love as a strategy. Commit to life. By following this framework of nonviolence, we co-create a world where conflict is transformed, not through domination, but through understanding – a world finally turning the page from a history of violence to a future of collective well-being and sustainable peace for all.

Sources:

By Prof. Luis Miguel GallardoFounder & President, World Happiness FoundationProfessor

I’m traveling in Vietnam now—the land that gave the world

Hanoi has a particular kind of energy in January—quiet streets