Swami Vivekananda Ji: A Living Impact on Strength, Service, and Inner Peace.

Swami Vivekananda Ji: A Living Impact on Strength, Service, and

“When our deepest need to belong is hijacked by fear, it can justify division and genocide; but when expanded through soul awareness, it becomes the force that reminds us we are one family, one humanity, one soul.”

Dedication

To all victims and survivors of terror, genocide, and systemic violence: This work is dedicated to your courage, your pain, and your unbreakable spirit. May the memory of those lost never be erased, and may the voices of those who survived be honored as sacred teachers of truth. Your suffering is not in vain — it calls us to awaken, to remember our shared humanity, and to act so that no soul is ever excluded, silenced, or destroyed again. In your honor, we commit to expanding the circle of belonging until it embraces all.

Why all this horror?

I have long been fascinated by the roots of peace and conflict. As someone deeply committed to understanding why human beings come together in harmony or fall apart in strife, I have found myself on a journey that goes beyond academic theory. The continuous struggles and violence we see around the world are not just headlines to me – they feel personal, fueling a determination to search for deeper answers. This quest has led me into the realms of soul research and spiritual practice, as well as the study of behavioral and cognitive biases that cloud our judgment. In essence, I am driven by a simple question: Can understanding the hidden forces behind our need to belong help us break the cycles of conflict? My exploration has woven together insights from spiritual hypnotherapy, family system therapy, and social psychology – seemingly disparate fields that converge on a profound truth about human nature. Let me share what I’ve learned about how our souls connect in groups, why we cling so fiercely to our “tribes,” how that instinct can turn to darkness, and ultimately, how a greater awareness of our shared humanity might heal the deepest divides.

One perspective that deeply influenced me comes from the pioneering hypnotherapy research of Dr. Michael Newton, who explored what our souls experience between incarnations. Newton’s Life Between Lives (LBL) case studies suggest that souls are not isolated travelers but move in soul groups or “clusters” on the other side. According to Newton’s findings, when we’re not embodied on Earth we return to a kind of spiritual home base – often a tight-knit cluster of around 15 kindred souls at a similar level of development. These soul groups function like intimate classrooms or families in the spirit world, providing support and jointly planning lessons for upcoming lifetimes.

Newton’s clients described how, before birth, they carefully choose the circumstances of their next life and even coordinate roles with other souls in their cluster, almost “like parts in a play,” to help one another grow. This means that some major life events – even our most painful trials or conflicts – might be agreed upon by our soul group in advance as challenges we will help each other face for the sake of mutual learning. In this spiritual view, the bonds of a soul group can span multiple lifetimes, with members taking turns playing different roles – family, friends, lovers, even adversaries – all to foster each other’s development.

From the LBL vantage point, earthly hardships and even human cruelty are seen in a much broader context. One of Newton’s clients, reflecting on the turbulence of life on Earth, put it poignantly: “It is a world of conflict because there is too much diversity among too many people,” yet “for all Earth’s quarrelling and cruelty, there is passion and bravery here”. In other words, souls understand that incarnating on Earth means we will encounter fear, conflict, and diversity – conditions which can catalyze growth in qualities like courage, compassion, and understanding. Newton found that souls who lived through especially dark human experiences (for example, those who committed grievous wrongs or acts of cruelty) do not escape the consequences at the soul level.

After death, such souls undergo intensive healing and strict review under careful supervision – essentially being “separated out… in a kind of purgatory” for a time. In Newton’s view, conscience resides in the soul: when a life has been dominated by negativity or “evil,” the soul itself feels the weight and must rehabilitate. Every action that violates love and ethics is taken very seriously in the afterlife. Ultimately, the LBL teachings imply that all souls – even those who were perpetrators or victims of terrible atrocities – will, after death, confront the full truth of their actions and strive to learn from them. From this higher perspective, our most painful conflicts on Earth are intense lessons that, over many lifetimes, push us toward greater love and unity.

If Newton’s work highlights our spiritual interconnections, the work of therapist Bert Hellinger sheds light on our very human need for belonging and how it can shape our conscience. Hellinger, the founder of Family Constellation therapy, observed that every family (or any close-knit group) is bound together by invisible bonds of loyalty. From infancy, we absorb the unspoken “rules” of belonging in our family system – learning by osmosis whom to trust, what to believe, and how to behave in order to be accepted. According to Hellinger, our sense of “guilt” or “innocence” is largely defined by these group norms. We tend to feel innocent – that is, at ease with ourselves – when we comply with the beliefs and rules of our family or culture, and we feel guilty when we defy them. In other words, our conscience often speaks with the voice of our group.

This reframing helps explain why ordinary people can commit or condone harmful acts yet not feel personal guilt: as long as those acts are sanctioned by their in-group’s ideology, the individual may internally feel “innocent” or even righteous. Conversely, going against one’s group – even to do what is objectively moral – can trigger profound guilt and anxiety because on a primal level it threatens one’s sense of belonging. I find this insight extremely illuminating: it suggests that what we call a guilty conscience might actually be an instinctive fear of exclusion from our tribe, more than an objective barometer of right and wrong.

Hellinger identified Belonging as one of the fundamental “Orders of Love” that govern family systems. In Hellinger’s view, there are three basic orders of love in any family or group: Belonging, Hierarchy, and Balance. Belonging means that everyone has an equal right to be part of the family or system – if any member is excluded or forgotten, the system falls out of balance. The family’s unconscious will actually seek to right that wrong. (The other two orders are Hierarchy – acknowledging the natural order of parents and elders coming before those who follow – and Balance – ensuring a healthy give-and-take in relationships. When these laws are disrupted, Hellinger noted, love cannot flow properly and the family will manifest pain until equilibrium is restored.)

The principle of belonging is so strong that if someone is cast out of the family’s story, later generations often subconsciously carry or re-enact the fate of those who were excluded as if compelled to fill the void and make the family whole again. Hellinger and others have observed many cases of a descendant inexplicably mirroring an ancestor’s suffering or wrongdoing that the family never acknowledged – a phenomenon sometimes called ancestral trauma. In one interview Hellinger gave an example: if a family had a child who died young and was then quietly erased from memory, a child in the next generation might unconsciously “follow” that fate – for instance, feeling an illogical urge toward death or despair – essentially living out the destiny of the forgotten child. The family “soul,” as Hellinger called it, cannot tolerate a member being lost; it will, in a sense, draft someone else to represent the lost member until that person is acknowledged and reintegrated into the family story.

Our need to belong is so fundamental that individuals will even sacrifice their own well-being or life out of loyalty to the group’s wholeness. For example, a child might subconsciously take on a parent’s illness or follow a parent into death, as if saying “I’ll join you in your suffering so you’re not alone.” Hellinger saw this as an innocent (though tragic) expression of love – the child’s soul believes this sacrifice honors the bond. Likewise, if an earlier family member caused great harm or carried heavy guilt that was never resolved, a younger member may self-destruct in an unconscious act of atonement.

Chillingly, Hellinger noted cases among the grandchildren of Nazi perpetrators who exhibited suicidal tendencies “to redress” the unresolved guilt of their ancestors. In one discussion, he remarked that many descendants of Nazi murderers, a generation or two later, felt a powerful urge to die – as if their souls were trying to pay a debt, taking upon themselves the fate that their ancestors never faced. All these patterns reflect what Hellinger called the “family conscience” or family soul at work. Its highest priority is not individual happiness or even individual survival, but the integrity of the group. Belonging, in this systemic view, truly is a matter of survival – on an emotional-spiritual level, being cast out of the family feels equivalent to death. So, people will obey the unconscious “orders” of their family or group, even to their own detriment, to avoid the unbearable pain of exclusion.

Human evolution has wired us to experience group belonging as a literal survival issue. In our evolutionary past, being banished from the tribe often meant death, so our brains developed to treat social rejection as an emergency. Even today, research confirms that the threat of losing our social connections triggers primal panic – a fight, flight, or freeze response akin to the fear of physical danger. In moments of crisis, this survival wiring tends to scale up to the group level. We instinctively rally to protect “our own” when we perceive an external threat. This solidarity can be positive (think of communities uniting after a disaster), but it also has a dark side. Hellinger pointed out that strong identification with a group can foster an us-versus-them mentality – what he termed “the dark side of belonging,” a battle for supremacy in which one group claims, “Our beliefs are better than yours. Our lives are more precious than yours.”.

When the need to belong warps into blind tribalism, our empathy for those outside the group diminishes, and nearly any action can be justified if it’s done in the name of defending “us.” We start to see our side as inherently good and any opposing side as inherently bad (or at least less deserving). At that point, the normal moral rules no longer seem to apply universally – they shrink to cover only our in-group. History gives us far too many examples of this. Leaders and ideologies throughout time have learned that by framing conflicts as life-or-death struggles for survival, they can hijack our tribal loyalty. When people truly believe their group is under existential threat – that “if we don’t fight, we will be destroyed” – an alarming transformation occurs: moral codes narrow, and harming the “enemy” comes to be seen not as wrong, but as honorable. In such circumstances, almost anything goes if it ostensibly protects one’s tribe.

I find it sobering how easily a noble cause can slide into cruelty when fueled by groupthink. As a systemic analyst, Kay T. Shoda, insightfully put it, “Many horrific deeds start with benevolence. A noble cause can make virtuous authoritarians of us all.” In other words, ordinary, good-hearted individuals – convinced they are serving a great good or righteously defending their community – may participate in atrocities with clear consciences. Their innate need to remain “innocent” in their community’s eyes (as Hellinger described) means that obeying the group becomes paramount – even if it violates basic humanity. I think about soldiers in every era who were told that the enemy was less than human, or citizens who turned a blind eye while neighbors were persecuted, because the authorities claimed it was necessary for the greater good. When we believe “we are the good guys and those others are pure evil,” we become capable of doing terrible things in the name of righteousness.

Psychologically, what happens is a kind of moral blindness: we shut off our individual sense of ethics and outsource it to the group’s orders and ideology. If the tribe says an action is virtuous (or at least forgivable in the context of war/defense), then our conscience – ever eager to conform – goes along. Those within the group who do sense something is wrong face immense pressure to silence their qualms, lest they be labeled traitors and risk ostracism. This dynamic can turn a whole community against an “enemy” and justify the unjustifiable.

There is also a contagious “herd mentality” that takes hold in heated group situations. In a crowd, personal responsibility diffuses and critical thinking can be overwhelmed by collective emotion. “Within every herd lives a certain kind of madness,” one commentator observed, noting that once we join a herd, we are “less inclined to question the orthodoxy of the herd.”. Dissent and nuance get drowned out by the louder chorus of consensus. We’ve all seen how otherwise rational individuals can get swept up in mob behavior or subscribe to extreme positions if those around them are doing the same. It’s as if being part of a large, unified group gives us a sense of strength and safety – we stop asking “Is this right?” and instead ask “Will this keep me bonded with my group?” And as that Knowing Field article pointed out, herds are quick to dismiss any challenge to their shared beliefs; questioning the group can brand you an outsider. In the rush of collective fervor or fear, atrocities can escalate rapidly, each person feeling less personally accountable (“I’m just following along with what everyone believes”). In this way, our beautiful, natural urge to belong and protect one another can be twisted into a force for exclusion, hatred, and violence when it falls under the spell of fear.

When the darkest side of group loyalty takes hold, the stage is set for genocide – the most extreme outcome of “us versus them” thinking. In a genocidal scenario, those in power systematically dehumanize a target population and convince their own populace that this out-group is an existential threat to their survival or way of life. Once the perpetrators’ collective conscience has been flipped in this way – rebranding mass murder as defensive necessity or even moral purification – the unthinkable starts to seem, to them, like the only viable course. It’s harrowing to realize how often ordinary people, under the sway of tribal fear, have carried out or supported genocidal acts.

The patterns are painfully similar: propaganda paints the victims as dangerous vermin or traitors, authorities proclaim that “we must act now or perish,” and the social pressure to conform does the rest. For example, Nazi leaders indoctrinated citizens with the notion that Jews were poisonous enemies of the nation’s survival; in 1994 Rwanda, Hutu extremists broadcast that the Tutsi minority were plotting to enslave and destroy the Hutu majority. Many who took part in the violence genuinely believed they were heroically protecting their children’s future or obeying a sacred duty. Under such conditions, moral disengagement becomes almost complete. It might sound paradoxical, but belonging to a self-declared “good” or victimized group can increase the likelihood of harming others. As a commentator in The Knowing Field noted, “Our belonging to a group that states we are the good ones, the innocent ones, the victims, is also the group most likely to harm others in the name of the cause.” When people are utterly convinced “we are innocent – they are evil,” they can perpetrate evil in the name of innocence.

Equally important in allowing genocide to unfold is the inaction of the wider community – the bystanders, both within and outside the society. Inside a society turning genocidal, many in the majority do not personally commit violence or even cheer it on, but they also do nothing to oppose it. This silent majority often feels powerless, afraid, or simply clings to normalcy and denial as long as possible. Hellinger’s concept of systemic conscience helps us understand that those who quietly disagree still often choose loyalty over resistance. They may sense the horror of what’s happening, yet fear being cast out of their community (or brutalized themselves) if they speak up. The result is that “the majority is silenced, it does not speak, it does not vote, it chooses not to take a side” in the face of mounting atrocity.

We saw this in Nazi Germany, where many citizens just kept their heads down; and in every other genocide, where large segments of society remained passive or paralyzed by fear. On the international stage, a similar dynamic often plays out. Outside observers frequently avert their eyes from a genocide in progress, especially when the victims are seen as “not our people.” Leaders rationalize their inaction by claiming the situation is too complicated, or by prioritizing political and economic interests. There is also a psychological numbing that happens when we witness extreme violence from afar. It can trigger a kind of shutdown or dissociation – a sense that the problem is so big and so far away that we have no power, so we tell ourselves there’s nothing we can do. In the blunt words of that article, “The mountain is too big to climb so why look at it.”

Many nations and individuals respond to genocidal crises with exactly that fatalistic shrug. We other-ize the conflict – viewing it as those people over there doing terrible things, not part of our world – which makes it easier to stand by. All of these factors contribute to the tragic pattern that genocides are rarely halted in their early stages by outside intervention. More often, they run their ghastly course until there’s nothing left to kill, leaving the rest of the world to ask after the fact: How could so many ordinary people go along with such horror? And how could so many others turn a blind eye?

Both Newton’s spiritual insights and Hellinger’s systemic approach ultimately point toward one thing: the need for a greater awareness of our interconnectedness. After the frenzy of group hatred and fear has passed – whether through the passage of time or the passing of lives – a deeper reality remains: we are not actually separate, competing tribes, but one human family. Hellinger observed that in Family Constellation sessions dealing with historical atrocities, something profound often unfolds when representatives of the victims and perpetrators are allowed to encounter each other simply as fellow humans, beyond the roles of “enemy” or “ally.”

Without any forced intervention, a movement toward reconciliation can arise spontaneously. He reported that when the dead victims and the dead perpetrators “face each other” on a level beyond life, all the notions of justice or vengeance that the living cling to seem to fall away. In one workshop, Hellinger described a powerful scene: representatives for those who were killed and those who killed them gradually moved toward each other and ended up lying down mingled together – “all dead in peace.” Even the representative of the chief perpetrator eventually lay down with his feet touching those of the leader of the victims, and there they remained, side by side in stillness.

Such images are striking and poetic – they hint that, from the perspective of the soul, perpetrator and victim are ultimately one. According to Hellinger, moments like these reveal the presence of a “greater force” or “greater soul” that encompasses both sides. It is as if the antagonists, when they step back far enough, become humble in the face of a unity that dwarfs their conflict. Hellinger concluded: “What unites all of them I call a greater soul… The soul is something that steers the course of history and personal life. And in this soul we participate. Instead of looking at the individual as having a soul, he participates in a soul.”

In other words, there is a collective soul – of a family, a nation, perhaps of humanity as a whole – of which we are all members. From that higher vantage point, the illusion of separateness that feeds hatred and violence dissolves: those who thought they were enemies discover they were intertwined parts of a larger whole all along.

Michael Newton’s findings resonate with this idea as well. His clients in deep trance often reviewed their lives – including lives in which they suffered greatly or caused suffering – with the help of wise guides and loved ones in their soul group. The emphasis was always on learning, accountability, and healing. Interestingly, Newton found that souls sometimes choose to switch roles in different lifetimes as part of their growth. A soul who played the role of a perpetrator in one life might deliberately incarnate as a victim in another life (or vice versa) to directly experience the consequences of those actions and develop deeper empathy. It’s as if, over many incarnations, each soul agrees to “walk in the other’s shoes.”

This notion – that we switch roles like actors across lifetimes – suggests a built-in path to understanding and forgiveness. If I know that in one life I was the oppressed and in another life I was the oppressor, it becomes clear that neither identity is the totality of who I am. On a soul level, we come to realize that we contain each other. Such a design, if true, implies that eventually all souls (and thus all people) will know both sides of every deep human experience. The perpetrator will know the pain of being helpless, and the victim will know the agony of guilt – until compassion blossoms.

This perspective does not excuse horrific actions in the moment, of course, but it places them in a continuum where redemption is possible and where love and unity are the ultimate destination for every soul. It aligns with the idea that even the darkest chapters of human history can, in the long arc of spiritual evolution, serve to push consciousness back toward the light – by showing us, in brutal fashion, the consequences of forgetting our oneness.

In conclusion, my exploration of these perspectives has taught me that while our primal need to belong can indeed lead to division and violence, it can also become the key to healing when we expand our understanding of who “belongs.” If we recognize how easily our survival instinct can be hijacked by fear-based group ideologies, we can become more vigilant against messages that demonize others and appeal to our worst tribal impulses. And by the same token, if we embrace the idea that at the deepest level we all belong to one human family – in fact, to one greater soul – then the justifications for excluding or exterminating any subgroup of people begin to collapse.

Genocides and mass atrocities happen when we forget our fundamental connectedness, when we shrink our circle of empathy to a select few and harden our hearts to everyone outside. Societies fail to stop these horrors when we see the suffering of others as “not our problem.” The antidote, I believe, lies in expanding our sense of “us.” We must extend that sacred circle of belonging to include all peoples, all faiths and ethnicities – to include, frankly, every living being. As Hellinger insistently taught, everyone has a right to belong, and only when we honor that truth – from our smallest family unit all the way to the family of nations – can the cycle of group hatred and violence truly be broken. This is not a facile solution; it requires great courage, humility, and awareness. But I am convinced that humanity’s survival, both physical and spiritual, depends on us remembering that we are ultimately one group, one soul. If we can ground ourselves in that larger identity, we may finally transcend the age-old struggle of “us versus them” and move toward a world rooted in compassion and peace.

Across the world, today’s conflict zones reflect the same dangerous dynamics that have fueled atrocities throughout history. In Israel-Palestine, cycles of historical trauma and fear have erupted into the dehumanization of the “other,” evident in the collective punishment of entire communities. In Russia’s war on Ukraine, state propaganda denies the very identity of Ukrainians, casting them as an existential threat to justify brutal persecution. Indigenous communities worldwide still confront erasure and intergenerational trauma in the long shadow of genocide.

Meanwhile, minorities from Myanmar’s Rohingya to China’s Uyghurs face systematic persecution that many recognize as genocide in slow motion. Even now, in parts of Africa like Sudan’s Darfur region, ethnically targeted massacres carry the unmistakable hallmarks of genocide. Despite different contexts, all these crises share a common root. Primal survival instincts and the human need for belonging have been twisted by fear and historical trauma into hatred, leading to a profound soul-level disconnection from our greater human “soul group” and the sacred truth of our shared humanity. Recognizing this pattern places an urgent moral and spiritual responsibility on each of us: we must awaken our conscience and spiritual awareness and step forward—consciously, compassionately, and in practical solidarity—to interrupt this cycle of violence now, before it deepens. Through a soul-connected lens that honors every life as part of one human family, we can transform collective trauma into collective healing, breaking the chain of atrocity and ushering in a new paradigm of belonging that protects and cherishes all.

#Belonging #SoulGroups #FamilyConstellations #LifeBetweenLives #MichaelNewton #BertHellinger #AncestralHealing #CollectiveTrauma #GenocideAwareness #StopGenocide #HumanRights #Peacebuilding #ConflictResolution #TraumaHealing #SharedHumanity #OneHumanFamily #GreaterSoul #Oneness #Tribalism #GroupConscience #SurvivalInstincts #MoralBlindness #NeverAgain #CompassionInAction #SpiritualAwakening #GlobalSolidarity #HealingTogether #LoveAndUnity #FundamentalPeace #Happytalism

Sources:

Swami Vivekananda Ji: A Living Impact on Strength, Service, and

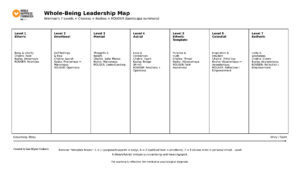

Introduction In today’s transformational leadership coaching, ancient spiritual models are

We are living through a time when pain is increasingly